A proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim?

A note on case-by-case assessment

One of the sticking points that I see regularly in the debate around single-sex services centres on the requirement in the Equality Act 2010 that the provision of single- or separate- sex services must be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. Some argue (often following advice issued by the Equality and Human Rights Commission) that this requirement means that it is unlawful to operate with a blanket rule excluding all men from women-only services. The EHRC Code of Practice on Services, public functions and associations contains guidance which states that

If a service provider provides single- or separate sex services for women

and men, or provides services differently to women and men, they should treat transsexual people according to the gender role in which they present.

On one interpretation of this view, a case-by-case assessment is required as this is the only way to ensure that the operation of the service is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

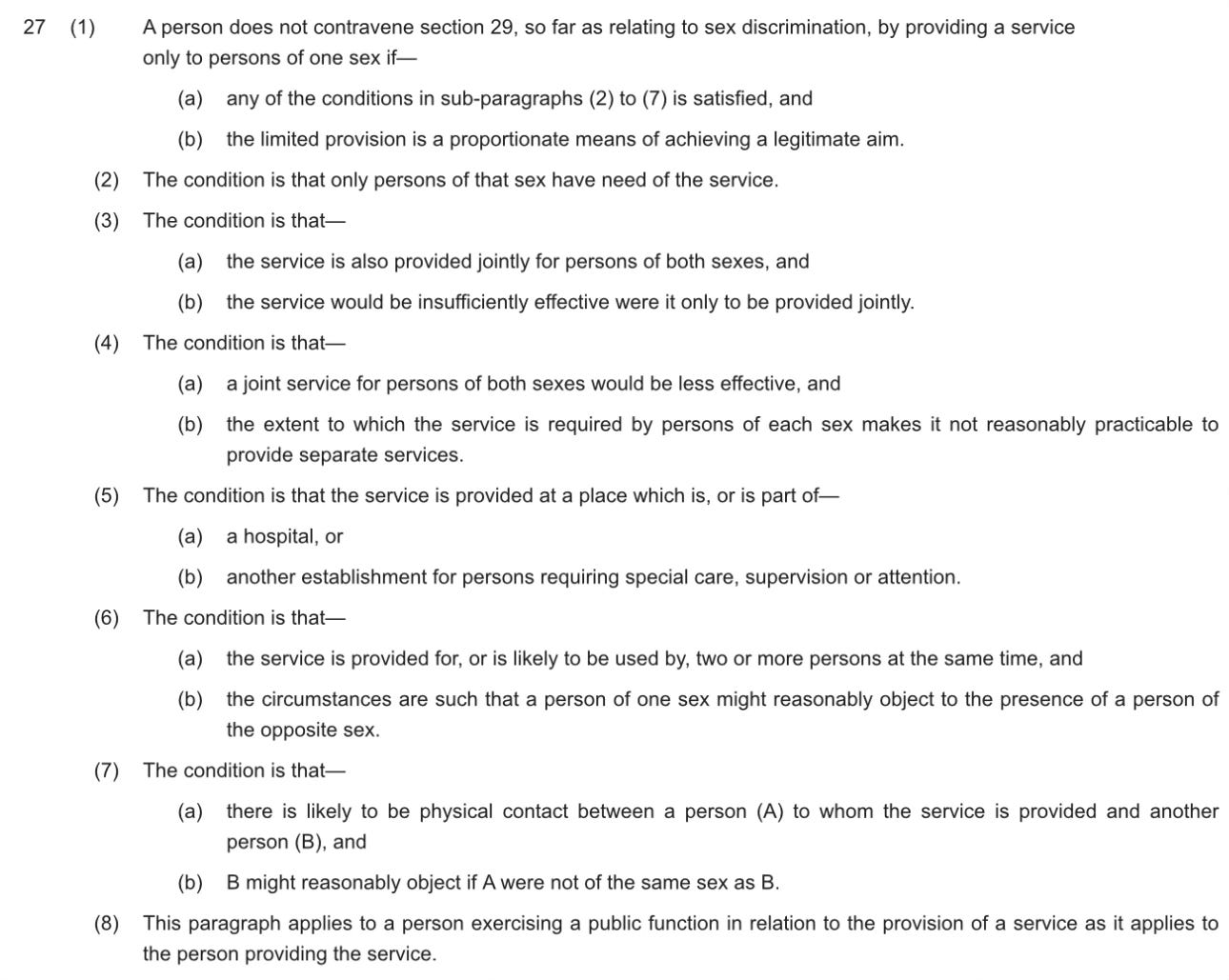

Let’s look at the single-sex exemptions contained in Schedule 3 of the 2010 Act:

This is effectively a generic proportionality test with the legitimate aims identified explicitly in statute. Sub-paragraphs (2) to (7) tell us what aims are legitimate for the purpose of this assessment. If the service meets one of these conditions, it satisfies the first part of this test.

The second part is where things become complicated, at least if one is not familiar with Supreme Court jurisprudence. Once the legitimate aim has been identified, the provision of single-sex services must nevertheless be proportionate to achieve that aim. This means that, depending on the aim, in some contexts single-sex provision will be entirely proportionate and in others it may not be.

For example, one of the conditions that can be established is that the service is provided in a hospital. But just because a service is being provided in a hospital does not make it automatically proportionate for it to be provided only to persons of one sex. Blood tests are a service provided in a hospital; that does not mean that it is proportionate to provide them only to men.

In contrast, cervical smears are also provided at hospitals but they are also a service where there is likely to be physical contact between a person (A) to whom the service is provided and another person (B) who might reasonably object if (A) were not female. In this context the provision of a single-sex service would be proportionate.

Crucially, in this context, there is no need to conduct a case-by-case assessment. The exclusion of all men from the provision of female-only cervical smears is entirely proportionate because the aim here - the protection of the rights and dignity of female patients requesting a female-only service - can only be achieved by a blanket policy: when a woman requests female-only care she receives female-only care with no exception. Anything less than that would be a gross violation of her rights and cannot be justified.

At the level of legal doctrine, there is nothing disproportionate per se about a blanket policy. The UK Supreme Court over the course of the last 20 years has repeatedly affirmed this position. For example in R (Begum) v Headteacher and Gvnrs of Denbigh High School [2006] UKHL 15 a blanket uniform policy was held to be proportionate notwithstanding the fact that one student wished to wear the jilbāb. There was no requirement on the Headteacher to conduct a case-by-case assessment, nor even to consider complex proportionality analysis at the level of granular detail:

“the focus at Strasbourg is not and has never been on whether a challenged decision or action is the product of a defective decision-making process, but on whether, in the case under consideration, the applicant’s Convention rights have been violated …. But the House has been referred to no case in which the Strasbourg Court has found a violation of Convention right on the strength of failure by a national authority to follow the sort of [full proportionality] reasoning process laid down by the Court of Appeal.”

The affirms the important principle that duty-bearers “cannot be expected to make such decisions with textbooks on human rights law at their elbows” [68]. What matters is the substantive outcome: the Convention “confers no right to have a decision made in any particular way. What matters is the result: was the right to manifest a religious belief restricted in a way which is not justified under article 9.2?” [68]. Employers and service providers cannot be expected to engage in full proportionality analysis every time they set or apply policy.

Most recently, the Supreme Court has affirmed this position in Reference by the Attorney General for Northern Ireland - Abortion Services (Safe Access Zones) (Northern Ireland) Bill [2022] UKSC 32:

“questions of proportionality, particularly when they concern the compatibility of a rule or policy with Convention rights, are often decided as a matter of general principle, rather than on an evaluation of the circumstances of each individual case. Domestic examples include R (Baiai) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2008] UKHL 53; [2009] 1 AC 287, the nine-judge decision in R (Nicklinson) v Ministry of State for Justice [2014] UKSC 38; [2015] AC 657, and the seven-judge decisions in R (UNISON) v Lord Chancellor (Equality and Human Rights Commission intervening) [2017] UKSC 51; [2020] AC 869 and R (SC) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions [2021] UKSC 26; [2022] AC 223.”

It is entirely within the discretion of employers or service providers to adopt general rules and policies. An assessment of these rules and policies can be done with regard to the rule or policy itself without the need to conduct a full proportionality test every time a rule or policy is applied.

So how do we make sense of the EHRC guidance which states that a case-by-case assessment is required? One way to explain this is that the guidance was about what the EHRC at the time considered to be best practice rather than legal obligation. That is entirely possible and indeed was part of the argument made by the EHRC in AEA v EHRC [2021] EWHC 1623 (Admin). Here, the EHRC argued that the use of the term “should” in its guidance meant that it was not stating legal obligation which would be connoted by “must”. It is therefore important to recognise that this argument rests explicitly on the claim that a case-by-case assessment is not legally required. Whether it is practical or desirable to conduct one every time a single-sex service seeks to exclude someone of the opposite sex is a different matter entirely.

When thinking about proportionality it is important to think about the reason why a service is being set up as single-sex or separate-sex in the first place. If the reason is tied to the fact that provision of a mixed-sex service would be ineffective, there may be less scope for a blanket rule than in contexts where absolute exclusion is necessary to protect the human rights of women.

That is the point where things get quite complicated, but but the idea that you can't have general rules at all has been consistently rejected by the Supreme Court and should not be taken seriously by those commenting on the law in this area.

The EHRC is recovering from the legacy of the former CEO David Isaac, who was also a chair of Stonewall: a fox in the henhouse. The guideline you quote is inoperable. I have always seen the Protected Characteristic of Gender Reassignment as confusing at best and unworkable at worst. A 21 year old man can simply say he intends to become a woman, make no changes to his appearance or dress, and for the next 50 years, say, insist on being called Sheila, referred to as 'she' and using the women's toilets and changing room. Anyone who doesn't play along with his game can be reported for discrimination under the PC of GR. The PC should properly have been called Pretend Sex. Utter madness.