Bloodless Bloodbaths

On the Importance of Symbolic Violence

There is something sweetly cathartic about a British election. The image of the next Prime Minister shaking hands with one of his seat challengers, a man dressed as Elmo, may be good for a lighthearted chuckle, but it is also a reminder that the occupant of the highest elected office in the land is, and will remain, beholden to his constituency. Premiership is no shield against the consequences of poor leadership, a point that Liz Truss will have felt keenly this morning, if she can feel anything at all at this point.

In our system, no seat is truly safe. The speed and ruthlessness with which results are declared encapsulates the brutality of this kind of democracy. Former and future cabinet ministers teeter on a knife-edge, many swept away in a tidal wave of change. Two months ago, these people ran the country. Now, they are watching as a political bloodbath is efficiently executed; the former Prime Minister presents himself before the King to fall on his sword before being whisked away in a removal van, his replacement quickly installed and a new cabinet chosen. In one sense, this is just business as usual. In another, the fact that the transfer of power can occur so seamlessly, is a testament to the resilience of (some) of our most important constitutional conventions.

The first-past-the-post system has plenty to be criticised for, but one thing that it does well is facilitate political symbolism in the form of genuinely crushing defeats. That shouldn't be underestimated: symbols are an essential part of any constitutional system, but they are of particular importance in a system such as ours.

In 1867, Walter Bagehot wrote in The English Constitution, that all constitutional orders need two parts, ‘one to excite and preserve the reverence of the population’ and the other to ‘employ that homage in the work of government’. This was the division between the dignified and the efficient aspects of the constitution. The classic embodiment of the dignified constitution is an ostensibly powerless monarch, who nevertheless preforms a vital function of representing political unity, unsullied with the cut and thrust of day-to-day politics. The efficient aspect was seen most in the executive, capable of actually doing something to further the public interest, but lacking the ability to rise above the fray.

To a surprising extent King Charles has managed to maintain this role of living embodiment of the nation. But watching this election unfold over the last day has reminded me that there is also an important symbolic function fulfilled by the brutality of this electoral system and the smooth transition of power despite that fact. I suspect that the two may well be connected; that a certain level of symbolic violence in political arrangements is a defence against election contestation. If you’ve just had your arse handed to you on a plate you’re probably not in the mood for an insurrection.

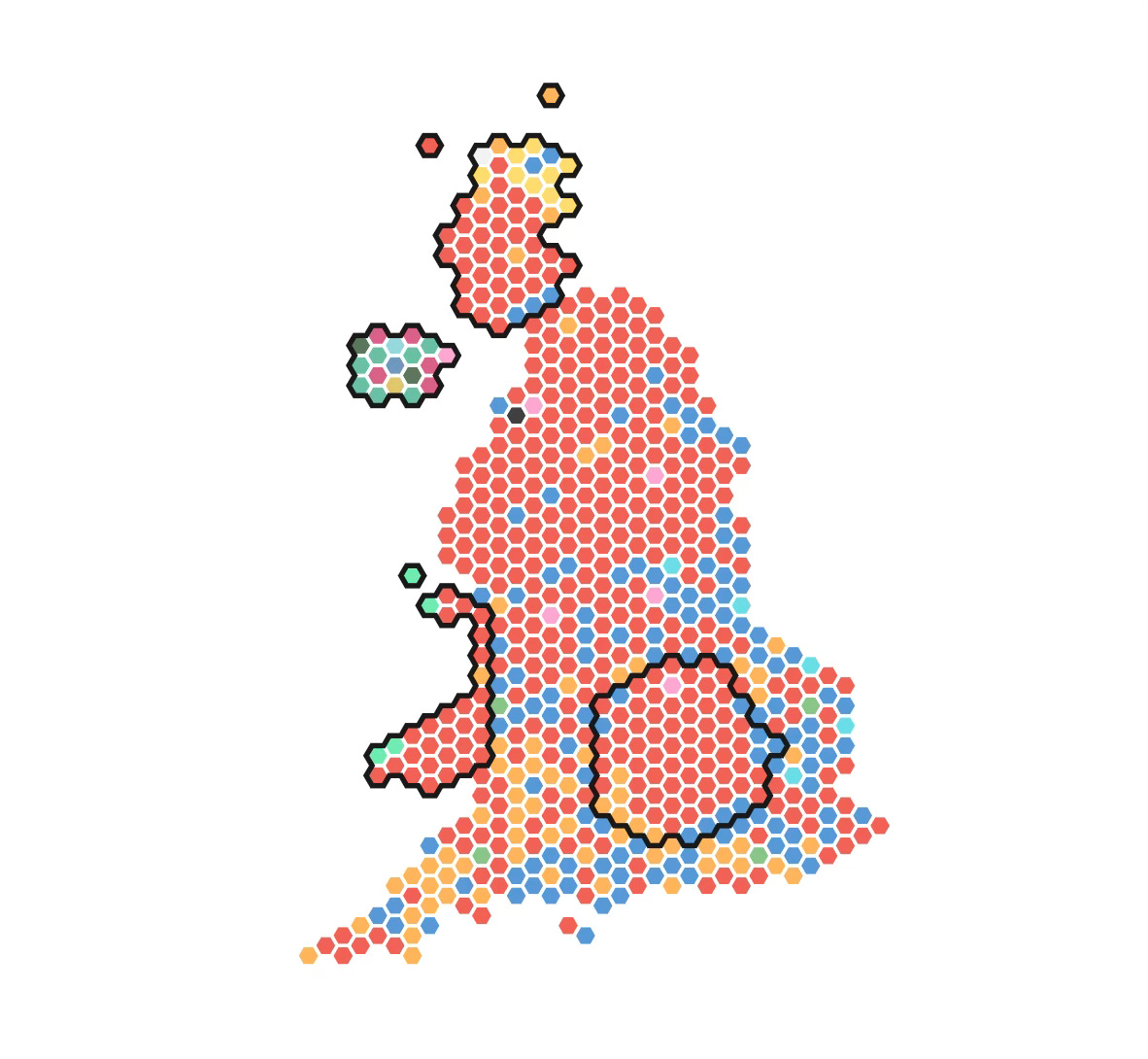

People are naturally talking about the huge win that the Labour Party has achieved. But this is nothing compared to the scale of the Conservative and SNP losses. Parliamentary parties have been culled in real time, on live television. We have subjected our political leaders to a sanitised pillory that unequivocally sent a message of repudiation and rejection.

Compare what happened last night to the 2023 Dutch election which came back with the right-wing populist Party for Freedom (PPV) earning the largest share of seats. What followed was seven months of negotiations to select a cabinet. The result was a four-party coalition led by a technocrat who isn’t leader of any of them. In one sense this is democracy in action when an electorate cannot agree. In another, it is the direct result of multiple parties tailored to niche preferences being presented to the electorate like items in a supermarket. On the surface that sounds great. Who could take issue with more tailored choices? But the consequence is that when a situation such as the 2023 snap election occurs, everything ends up being settled by horse trading. Contrast this to our system: today we vote, tomorrow the feckless wonders are on their way out.

Symbolically all of this is important. It provides a mechanism for people to get out some of their anger and to see genuine consequences for political failure. An election such as this is a release valve. It takes some of the built up pressure out of the system. People who have felt disillusioned with politics can sit back and bask in the warm glow of political evisceration. That helps to reset political dissatisfaction in a way that other systems may struggle with.

I don’t wish to overemphasise this point, however. It may be that this symbolic violence can help to guard against the rise of genuine political violence, but that is by no means a guarantee. Even if it were, this all depends on existing constitutional conventions being maintained and a level of professionalism achieved and respected.

Given the turmoil of western politics over the last decade, there was something shockingly refreshing about Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt graciously accepting defeat, congratulating Kier Starmer and complimenting him on his character and dedication. Constitutional symbolism and losers consent worked well last night. If the election campaign period had reflected the dignity shown in those moments, I would be feeling confident about the stability of politics going forward. But it didn’t.

Shamefully irresponsible rhetoric and a complete failure to take seriously threats and intimidation of female candidates should remain as a stain on any back-slapping that is being done today about the future of British politics.

Symbols are powerful. Action - and inaction - sends a message. The dismissal, glorification, and even encouragement of political violence against women must be called out by every public commentator discussing this election. Anything less is an insult to the memory of Jo Cox and David Ames.

Thinking also about the symbolic (mild)humiliation that is inflicted on the victor, by requiring them to begin by visiting and acknowledging the monarch before they start governing. Some would read this as an outdated feudal hangover. More positively, I would suggest, it's a reminder both of the web of constitutional norms within which the successful party must operate, and of the truth that the victor must govern for the common good not simply for their own faction.

Blair in his memoirs records his impatience with all of this tradition and ceremony when he won the 1997 election. He wanted to get on with the business of governing.

Yeats is wiser here:

"How but in custom and in ceremony

Are innocence and beauty born?"