Disinformation and The Good Law Project

Public discussion of the law relating to sex and gender identity is often polarised. Rarely do those who disagree about this topic adopt the same interpretation of the law. This is a complex area of law that often leaves significant room for reasonable disagreement. It is therefore incumbent on those of us engaged in this debate to approach it in good faith and with due academic charity. It is rarely appropriate to attack someone’s motives or their personal circumstances in lieu of substantive engagement with the points of legal disagreement.

Sometimes, however, the claims that individuals or organisations make are so radically detached from any plausible interpretation of the law that it becomes impossible not to wonder whether this is wilful disinformation.

The Facts

This week, the High Court dismissed a judicial review brought by The Good Law project against interim guidance issued by the Equality and Human Rights Commission on the law relating to single-sex spaces following the Supreme Court decision in For Women Scotland v The Scottish Ministers. I’ve written a detailed summary of the judgment, available here.

In brief summary, the High Court rejected every claim brought by The Good Law Project and upheld the lawfulness of the interim update, concluding that it contained no errors of law. The following points made in the update were all held to be accurate descriptions of the law:

Workplaces

(i) Single-sex lavatories must be provided in workplaces.

Services

(ii) So far as concerns provisions on services in EA 2010, there is no requirement to provide single-sex lavatories.

(iii) Provision of a single-sex lavatory is permitted by the EA 2010 if that is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

(iv) Failing to provide a female single-sex lavatory could comprise indirect sex discrimination against women.

Workplaces and services

(v) Single-sex lavatories will cease to be single-sex if transsexual persons are permitted to use them other than in accordance with their biological sex.

(vi) If trans women are permitted to use a single-sex female lavatory, all biological males must be permitted to use that lavatory.

(vii) In some circumstances equality law may permit transsexual persons to be excluded from single-sex lavatories that correspond to their biological sex.

(viii) Lavatories in lockable rooms used one person at a time can be used by anyone.

(ix) If you provide single-sex lavatories do not fail to make provision for transsexual persons.

(x) If you provide single-sex lavatories (or other facilities), where possible also provide a mixed-sex facility.

The High Court made no finding that anything in the interim update was unlawful. It made no findings in relation to the EHRC Code of Practice which is awaiting a decision from Bridget Phillipson as to whether or not she wishes to lay it before Parliament. The Good Law Project failed on every ground of challenge it brought. The case was dismissed and the High Court concluded that The Good Law Project did not have standing to bring it in the first place.

The Good Law Project’s Reporting

Despite the resounding loss, those reading the Good Law Project’s reporting of the judgment may be forgiven for thinking that the High Court made findings that it did not make. That is because the Good Law Project have claimed that the High Court made findings that it did not make.

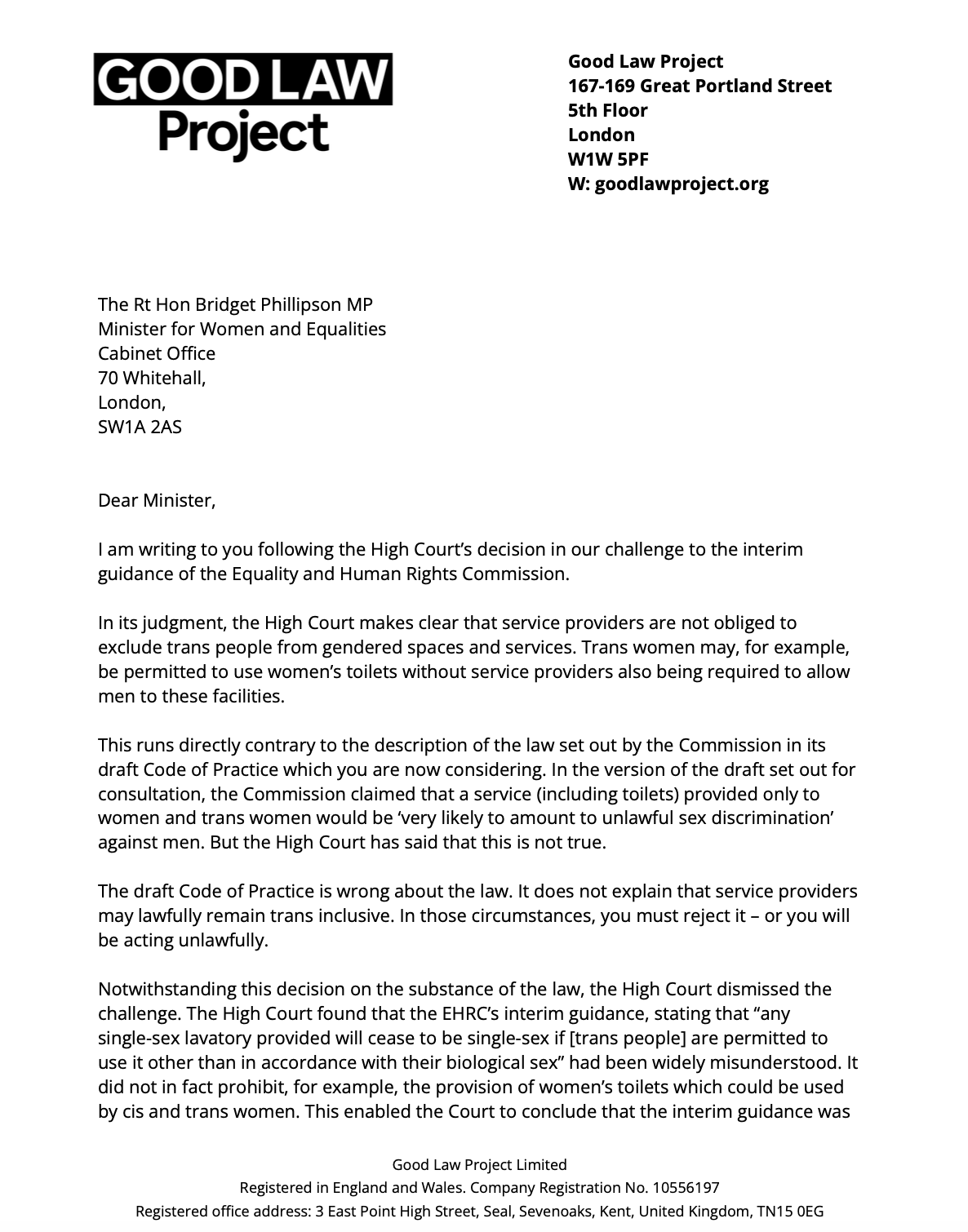

A few hours after the judgments publication, Jolyon Maugham, Executive Director of the Good Law Project sent the below letter to the Minister for Women and Equalities:

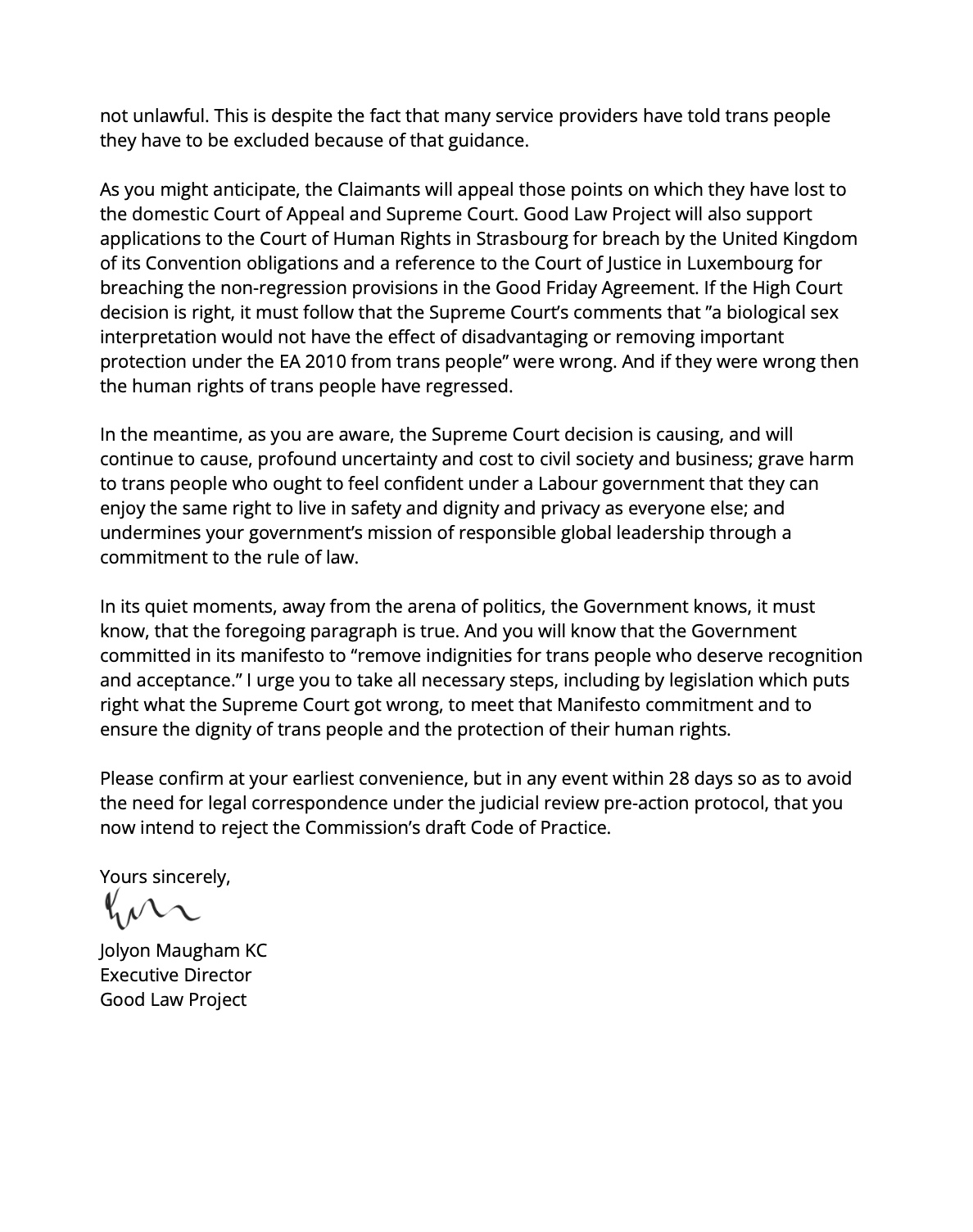

The GLP then posted on X that Phillipson is now legally required the reject the EHRCs draft Code of Practice:

Obviously, the judgment this week did not pertain to the Code of Practice. It pertained to the Interim Update that set out the EHRCs understanding of the law which then informed the Code of Practice. That interpretation of the law was upheld as legally accurate by the High Court. The High Court did not make a finding that service providers are not obliged to exclude trans women from female only services. The High Court did not make a finding that trans women may be permitted to use women’s toilets without service providers being required to allow men into those facilities. It did not make a finding that service providers can lawfully operate women only services so as to include trans women. The High Court made no findings about aspects of the Interim Update being “widely misunderstood”. Having not made any finding about aspects of the update being widely misunderstood, it did not use that as the foundation for a conclusion that the update was lawful.

Given the fact that the High Court upheld the legal accuracy of the claims made in the Interim Update and given the fact that the Code of Practice is based on that interpretation of the law, it is staggeringly unclear how the Good Law Project could claim that the Minister is now under a legal obligation to reject the Code. There is simply no foundation in the findings of the Court to support this claim.

The Spin

While there is nothing in the findings of the High Court that could justify the claims that the Good Law Project has made in this letter, a closer look at their FAQs update, published shortly after the judgment, may shed some light.

Looking at these FAQs, it is clear that the GLP has chosen to draw its conclusions about this judgment, not from the findings or conclusions of the Court, but from highly selective excerpts from the reasoning, taken out of context.

Below is a collection of examples of this happening.

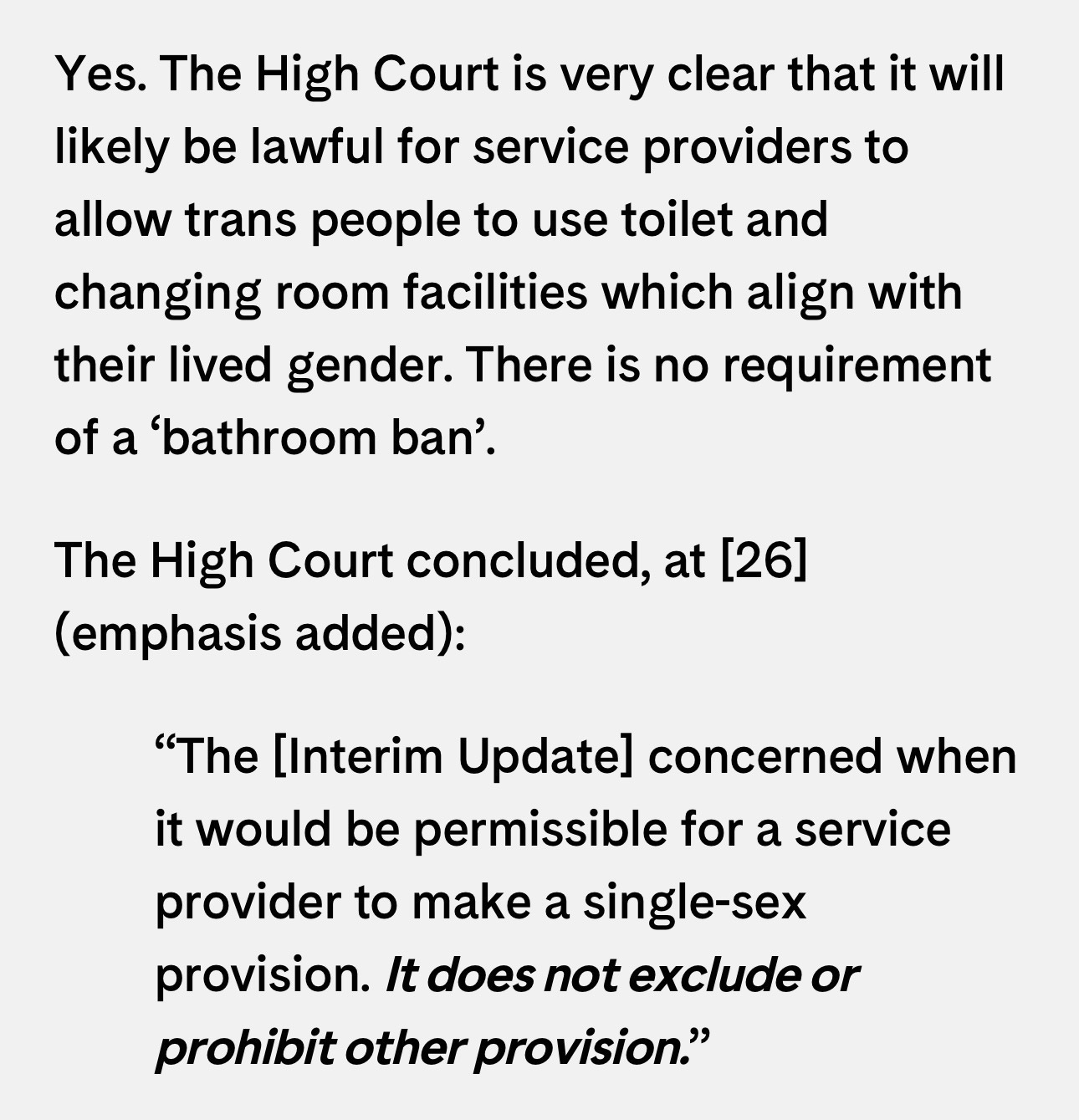

In response to the question “Is it lawful for service providers to allow, for example, trans women to use women’s toilets and changing rooms (and vice versa for trans men)?” the GLP states:

An astute reader will notice that this quote from [26] doesn’t say that it will likely be lawful for service providers to allow trans people to use single sex facilities which align with their gender identity. Given the fact that GLP have stated that the High Court was clear about this point, it’s odd that no quotation to that effect is provided. That is because the judgment contains no statement to this effect.

The statement at [26] merely states that service providers may provide single sex provision or they may provide mixed sex provision depending on the circumstances.

The GLP then continue:

It is important to set out clearly the context of what the High Court was discussion in this paragraph before examining what the GLP claims this means.

This paragraph appears in the context of the Court assessing the legal accuracy of the claim in the Interim Guidance that if trans women are permitted to use a single-sex female lavatory all biological males must be permitted to use that lavatory.

The premise of this point is that a man excluded from a female-only lavatory that allowed trans women access would succeed in a claim of direct sex discrimination. Swift J concluded that a successful claim would depend on the facts of an individual case, but that

there would, in principle, be scope for a strong argument that a rule or practice that permitted trans women to use the ‘female’ lavatory but required other biological men to use the male lavatory would comprise different but not less favourable treatment on grounds of sex. However, the circumstances of the case would be decisive. (For the purposes of the EA 2010 the lavatory would be mixed-sex, but for the purposes of the Claimants’ submission in this case it would still be labelled ‘women’.) [61]

It is important to be clear what Swift J did and did not say in this paragraph. This was not a conclusion about anything other than the argument that could potentially be made in response to a hypothetical claim of sex discrimination brought by a man excluded from trans inclusive ‘female’ lavatory. Nothing in this paragraph implies that such a lavatory would be lawful, even if the sex discrimination claim brought by an excluded man failed. Swift J did not say that it would fail. All he said here is that there is scope for a strong argument that a sex discrimination claim brought by a man might fail. If it did, the lawfulness of allowing trans women to access female-only facilities or services would depend on other applicable law, including the 1992 Regulations and the claims that could be brought from female service users based on sex discrimination and the Human Rights Act.

It is important also to read this paragraph in conjunction with the following paragraph at [77]

While I am less certain than the Interim Update that a man prevented from using the Claimants’ trans-inclusive female lavatory would be likely to establish the less favourable treatment necessary to make good a claim of direct sex discrimination, I do not consider that the way the point is put in the Update is necessarily wrong. Rather, it is a point that may turn on the facts of a situation. Even though the EHRC’s obligation when exercising its power under section 13(1)(d) of the EA 2006 is to provide an accurate statement of the law, the court must apply this requirement recognising that any statement of law will rest on some assumption of fact, even if only generic. Where a body such as the EHRC has issued guidance that rests on factual premises that are permissible, the court should hesitate before concluding that the guidance as issued was unlawful. Thus, I do not consider that the EHRC’s approach to point (vi) gives rise to any legal error.

The fact that there may be an argument advanced in a hypothetical case that could offer a defence to a claim of sex discrimination brought by a man was not sufficient for Swift J to conclude that the statement ‘if trans women are permitted to use a single-sex female lavatory all biological males must be permitted to use that lavatory’ was incorrect as a matter of law.

Jolyon Maugham, in his letter to Bridget Phillipson explains Swift Js finding here as arising from a finding that aspects of the Interim Update were widely misunderstood. He then claim that this enabled the Court to conclude that the update was lawful. That is simply not true. The Court made no finding that the Interim Update had been widely misunderstood. The conclusion that the update was lawful arose from Swift Js finding that the guidance did not contain any legal errors, even if the claim about a successful direct sex discrimination claim brought by a man was one lawyers could reasonably disagree about.

Give all of this, it is striking that the Good Law Project omit any reference to [77] in its FAQs and instead state the following immediately after quoting [61]:

Paragraph [61] clearly does not mean that service providers may lawfully provide women’s toilets for both women and trans women. That is simply not what paragraph [61] is about. All that can be inferred from what Swift J said in [61] is that he thought that, depending on the circumstances, there may be a strong defence available to a service provider seeking to defend a direct sex discrimination claim brought by a man excluded from a trans inclusive women’s service. That does not imply that operating such a service is lawful. Swift J made no findings to that effect.

Contrary to what the Good Law Project claim, the High Court did not explicitly state that it is permissible for service providers to label trans inclusive facilities as simply ‘men’s’ and ‘women’s’.

It is telling that, despite the Good Law Project referencing [61] to support the claim that the High Court clearly stated this, does not provide the text of the judgment where the Court supposedly clearly stated this. The relevant part of [61] reads:

However, the circumstances of the case would be decisive. (For the purposes of the EA 2010 the lavatory would be mixed-sex, but for the purposes of the Claimants’ submission in this case it would still be labelled ‘women’.)

Swift J was not making any findings of law here. He did not state that it was legally permissible to operate trans inclusive services or that it was legally permissible to describe such services as men’s and women’s services. All thay Swift J said on this point was, in a hypothetical litigation involving a challenge to the lawfulness of a trans inclusive women’s lavatory, that lavatory would be mixed sex but in the language of the Claimants submissions, the lavatory would still be labelled ‘women’.

The Good Law Project have taken a reference in the judgment to the ways in with their own submissions used language which departed from the legal meaning in the Equality Act and have presented it as a clear statement from the High Court that it would be legally permissible to operate a women’s service on a self-identification basis and continue to label it as a women’s service. That is misleading in the extreme.

There are two explanations for this. Either Jolyon Maugham and the Good Law Project are incompetent or they are wilfully spreading misinformation about this judgment. Personally, I find it hard to believe that this is mere incompetence. Either way, the result is the same: many people who haven’t read the judgment or who wouldn’t have the skills to understand it if they did have taken their lead from Maugham and the Good Law Project and have come away with a radically ill-informed understanding of the law.

I fear I’m starting to notice a pattern…

Thank you.

Given how reluctant Bridget Phillipson seems to be to lay the EHRC Guidance before Parliament, I am nervous that letter from the Good Law Projecf will lead her to delay still further.

Might it be appropriate for a group of experts in equality and human rights law, such as yourself, to write to Bridget Phillipson expressing your concern that misinformation by the Good Law Project is unhelpful and likely to lead to misunderstanding?

Fantastic analyses as always Michael, thank you!

Similar to Bronwen’s comment above, very much hoping that you and/or Sex Matters would be able to correct the GLPs deliberately misleading interpretation via a letter to Bridget Phillipson, they simply should not be able to get away with it, and BP should be given no fuel to further delay